100 years of the Mexico City Building Code

Spatial Scale: Urban

Temporal Scale: 100 Years

The first Mexico City Building Code (MCBC) was enacted after one of the first deadly earthquakes after the end of the Mexican Revolution, and marks the institutionalization of construction regulation in the country. The numerous revisions of the MCBC suggests a pattern: they are drafted and published after a strong earthquake reveals previously unknown effects of seismicity upon structures, and are therefore attempts to address engineering and institutional failures to avoid future repetition. However, based on the survey of the force of desiccation, for the MCBC, Mexico City’s soil remains a static object to be controlled, rather than a fluid and dynamic agent. [10]

Below is a spreadsheet which provides an overview of the context, developments and how each revision succeeds–of fails–to address seismic vulnerability. The table is not meant to be comprehensive, but to highlight (in red) aspects present in the building codes as they relate to and describe aspects observed in AO286, which was built with the 1957 MCBC, and collapsed under the validity of the 2016 revision.

AO286's 6th Slab

Spatial Scale: Architectural Detail

Temporal Scale: ~20 years

Based upon the available information made public in other investigative reports, interviews with stakeholders who include journalists, people who participated in rescue efforts on the collapse site, structural engineers and experts in seismology, this investigative platform presents a recreation of AO286 to highlight effects of tectonics, desiccation and regulation on it. Since architectural documents, such as plans, are unavailable, these are reconstructed from limited source material, such as a single floor plan, testimony from witnesses, photographs from the collapse, and technical reports contained in the case file obtained through Freedom of Information Requests.

When AO286 collapsed, the evidence strongly suggests that it's 6th slab was originally its topmost roof slab, inferring that the 7th floor was added after its initial construction. Based on the following images, an architectural detail of the 6th slab is presented. It is worth noting its unusual thickness, it's double construction with middle insulation and slopes, most likely for rain drainage purposes.

Facade of collapsed AO286, highlighting separation with AO284.

Detail of adjacent building separation, showing less than compulsory 50 mm.

7th and 6th slab, notice the difference between the construction of both.

6th Slab, notice the double layer with an intermediate fulling of soil-like material.

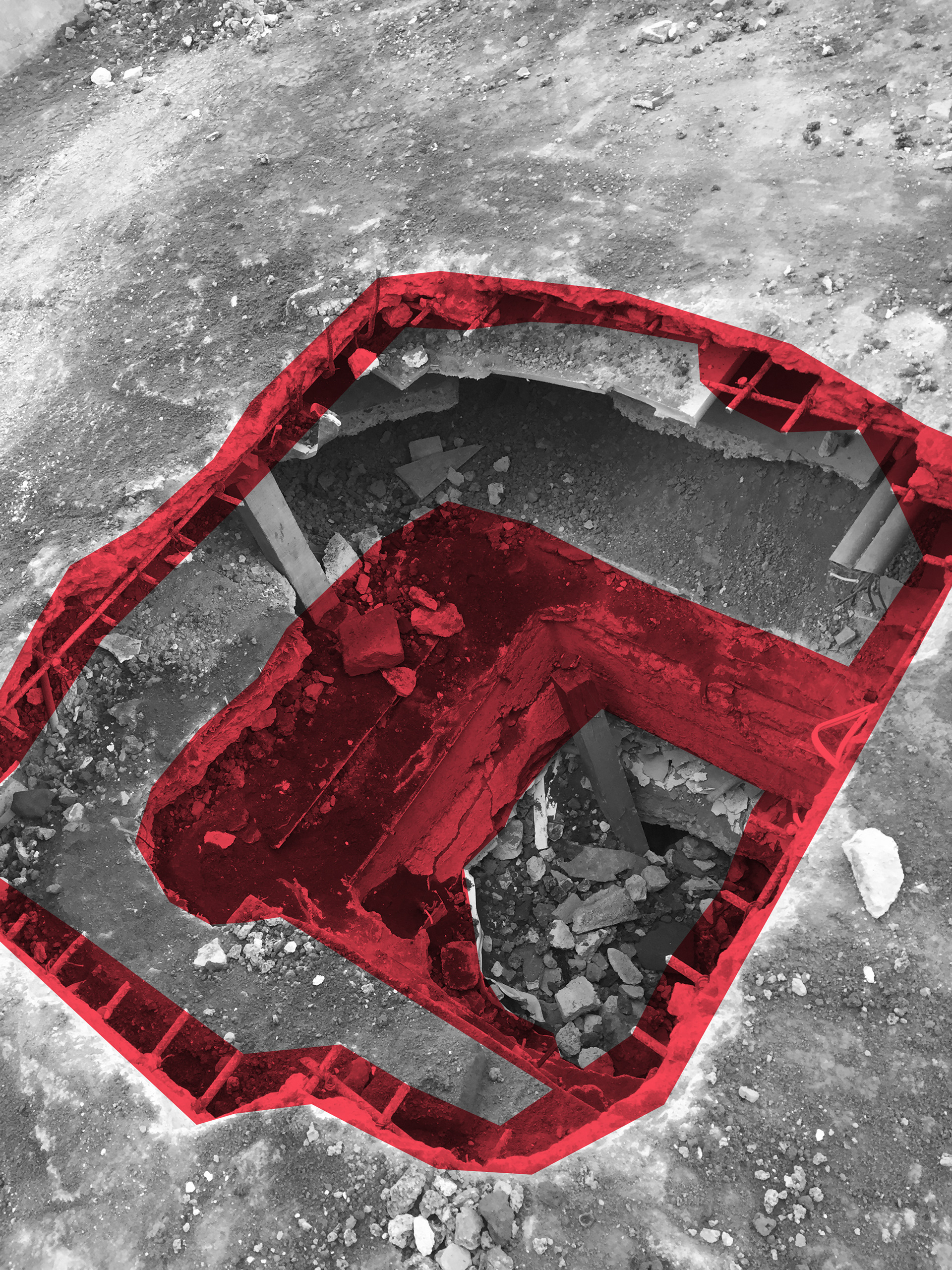

Collapsed 6th slab.

Removing the 6th slab.

Removing the 6th slab.

Measure tape next to collapsed column.

Measure tape next to collapsed column.

This architectural detail provides a 1.00 x 2.00 m. representation of the AO286's 6th slab. It was reconstructed from a number of interviews with engineers and rescuers present at AO286's collapse. Through their situated testimony, the degree of AO286's non-compliance with the MCBC acquires a material and aesthetic register, which may be deployed as forensic evidence in court.

Explore the resonance of the three forces:

Database

You may download the Mexico City Building Codes (MCBC) from 1921-2017 here.

Reconstructed architectural representation of AO286, redrawn from limited available architectural plans and a 3D BIM model, may be downloaded here.

Bibliography:

[10] Alcocer, Sergio M., and Víctor M. Castaño. “Evolution of Codes for Structural Design in Mexico.” Structural Survey 26, no. 1 (March 1998): 17–28. https://doi.org/10.1108/02630800810857417.

Garrocho, Carlos, Juan Campos-Alanís, and Tania Chávez-Soto. “Análisis espacial de los inmuebles dañados por el sismo 19S-2017 en la Ciudad de México.” Salud Pública de México 60, no. Supl.1 (March 1, 2018): 31. https://doi.org/10.21149/9238.

Reddy, Elizabeth. “Crying ‘Crying Wolf’: How Misfires and Mexican Engineering Expertise Are Made Meaningful.” Ethnos 85, no. 2 (March 14, 2020): 335–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/00141844.2018.1561489.

Roeslin, Samuel, Quincy T. M. Ma, and Hugón Juárez García. “Damage Assessment on Buildings Following the 19th September 2017 Puebla, Mexico Earthquake.” Frontiers in Built Environment 4 (December 4, 2018): 72. https://doi.org/10.3389/fbuil.2018.00072.